- The Westshore

- Posts

- Droughts, atmospheric rivers, and growth are playing havoc on our bedrock aquifers

Droughts, atmospheric rivers, and growth are playing havoc on our bedrock aquifers

It’s notoriously hard to find water in the Westshore, and getting harder

Even in a lush rainforest, water isn't a given. (📸 James MacDonald/Capital Daily)

Most people who live in the Westshore don’t have to think twice about drinking water and long, hot showers. They’re the majority who are conveniently connected to the Capital Regional District’s water supply, which comes from large reservoirs.

But there are several thousand people who use wells. Records show at least 2,400 wells in the Westshore, though there are many more that are unregistered. Almost all tap into either aquifer 606 that stretches underneath Sooke, Metchosin, Langford, and Colwood, or the 680 with underlies Highlands, Saanich, and Victoria.

Both are bedrock aquifers, one of two types that exist in BC. Water drains through the ground into cracks and fissures in the bedrock hundreds of feet below the surface, and seeps into wells drilled all over the Westshore.

Bedrock aquifers are highly reactive to weather: they fill up quickly when it rains, and drain relatively quickly in dry periods. The other type of aquifer in BC is made up of sand and gravel. Those have a more gradual reaction to rain and drought: water collects slowly and drains gradually. A sand and gravel aquifer might peak in February and gradually diminish until the fall, where a bedrock aquifer starts recharging within hours of a heavy rainfall.

This summer, the south coast had 104 days of sun between rainfall of more than one millimetre.

For the thousands of households that rely on water from the bedrock aquifer, that long dry stretch meant they had to call on outside sources for water.

“I don't know if a lot of people even know when they’re running low. The majority of people honestly just turn on their tap and it shoots air, and they're like, ‘Uh oh,’ and they call me,” said Nick Leslie, new owner of South Island Water who delivers drinking water by truck.

Even though this year has been nothing compared to the water demands of last year’s heat dome, Leslie has doubled the size of his fleet from three to six trucks since he bought the company mid-pandemic, and plans to double it again over the next few years. It’s clear from his business plans that he sees a need for water that doesn't come from the aquifers.

“More people are drilling wells. The way I put it is, you can only stick so many straws in the milkshake before nobody gets a sip,” said Leslie.

Gord Baird is a councillor in the District of Highlands, sits on the Capital Regional District’s Regional Water Supply committee, and designs rainwater harvesting systems for a living. This October when we were enjoying balmy, unseasonable weather, Baird was looking at water levels.

“Because we had a wet spring, cool temperatures, and lots of rainfall in the early summer, the CRD watersheds are actually doing really well. But in the Highlands, I have never seen so many people seeking to get water delivered,” he said. “I think it's gone long enough where people have used up their stores in their wells and they're searching out to get some make-up water brought in.”

This makes sense to hydrogeologist Mike Wei, who is the retired director of BC’s groundwater program. He still works as a consultant for water resource planning, and is an associate professor at the University of Victoria.

He says bedrock aquifers tend to be less productive than sand and gravel systems but the “rocks around Metchosin are notoriously uncracked. Fractures are few and far between.” It’s the cracks and fissures that hold water. Without them there’s no aquifer. It’s just rock.

Comparing data from wells on the Saanich Peninsula to those in the 606 shows two key differences: how deep you have to drill to get water, and how fast water fills the well.

“Whereas in Saanich you could probably get enough water for a household by drilling to 200 feet, you might have to drill to 1,000 feet in order to get to the fractures in Metchosin,” Wei said. “And whereas in every other area drillers report the well to be two gallons a minute, you’ll notice a lot of the well records [are] reported in gallons per hours.”

(Even though we’re on the metric system, well productivity is measured in US gallons per minute, USgpm.)

On the peninsula, Wei says the rock is dry and brittle so there are plenty of cracks and fissures that hold water. An observation well at the Victoria Airport that taps into aquifer 608, which covers most of the peninsula, shows a yield of 15 USgpm.

Over in Sooke, the 606 observation well yields just one gallon per minute. Hundreds of private wells in Metchosin, Sooke, and Highlands fill at fractions of a gallon per minute, or even have a “zero” where there should be a number of gallons—because by the time the drillers finished their report there still wasn’t any water in the well to measure the flow rate.

The deepest registered well in the Westshore is 1,500 feet near Matheson Lake. It yields a quarter of a gallon a minute. That’s less than one litre a minute.

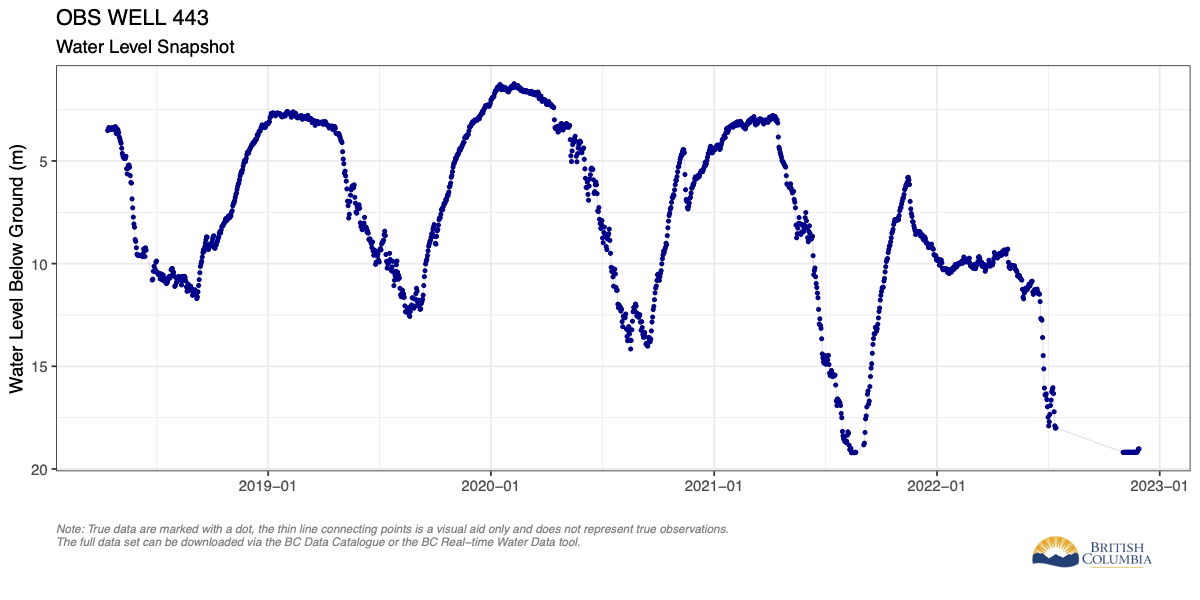

What’s more telling is that yearly data shows the 606’s cyclical annual water level decreasing over the last four years. It naturally drops each summer and fills up over the winter, but has gotten lower than ever the last two summers. The 680 has remained steady.

Water levels as recorded at the 606 aquifer observation well, located in north Sooke. (BC Government)

Aquifers are a constraint on development, until there’s another way to get water

Drilling that deep is not cheap, and there’s no guarantee of finding water. It’s another reason demand for Leslie’s trucks is going up.

“A lot of these people go and build their dream home but shy out on drilling a well because it's $40,000 to $50,000, and it's not a guarantee they will get water. I know a lady who spent close to $100,000 before she hit water,” he said.

For places that don’t have the option of piped water, the cost of drilling and the risk of drilling to a dry rock is making bulk water—trucked water that’s poured into household reservoirs—an attractive alternative to get water.

As a councillor, Baird and his colleagues think a lot about how much population growth the 680 aquifer can sustain. It has been the constraining factor for densification in Highlands, especially for deciding whether and how to allow secondary suites, which is a pressing issue for Highlands council.

Council is starting to consider whether aquifer recharge rates in certain areas should limit where secondary suites are allowed. It’s a hard question to answer, because there’s only one observation well for the whole 680 aquifer, and within Highlands there’s a variety of recharge rates. But it gets even more complicated since the provincial government has allowed different water sources to supply homes, such as bulk water and rainwater harvesting.

The province has been expanding the source water over the past few years. In 2016 it legalized composting toilets and greywater systems for water conservation, then in 2018 Canada and the US released standards for rainwater harvesting for commercial, multifamily, and residential buildings. That led the province to establish guidelines for rainwater being used as drinking water, which has led to an increase in rainwater harvesting for detached homes.

Baird designs rainwater systems for a living, so he should be thrilled—but he’s also concerned.

“It removes some of the development constrictions that could be placed on a parcel of land, and that is problematic in my opinion, despite the fact that I design systems, because there are probably places that should not be developed that are being developed because they've got access to rainwater rather than well water,” Baird said.

Risks to the aquifer: recharge, contamination, and withdrawal

On Oct. 4, 2022 a small fire broke out in the Highlands forest along Finlayson Arm. It was small, quickly contained and under control within days, but seriously underlined concerns about aquifer contamination. (📸 James MacDonald/Capital Daily)

When The Westshore first spoke with Baird about the state of groundwater in Highlands during the first week of October, it hadn’t rained more than one milimetre in 87 days. He had three concerns. His first was about the changing rain pattern. Climate change is causing more heavy rain over shorter periods of time, which impacts how water tables absorb and recharge.

“The benefits of a slow steady rainfall is it gives water a chance to sink into the aquifer and recharge it better. When we have heavier rainfalls, we get higher surface flows and higher runoff, and therefore the water that lands on the ground rather than getting a chance to sink in, actually flows over ground and drains through to the watersheds to Craigflower and Millstream.”

Wei the hydrologist concurred with this. “During really dry times and like during forest fires, when your soil is so dry, it can actually become water-hating, not water-liking. It's almost like the soil has a bit of a wax coating on it, and the water tends to run off.”

Contamination is the next issue Baird raised. The 606 aquifer is considered highly vulnerable to contamination—which is not a reflection on land use or activity in the area, just that the aquifer is close to sources and if there is a contamination issue, it will be vulnerable. The 680 is listed as moderately vulnerable.

“So if there are, for example, say a wildfire outbreak or conflagration event where retardants have to be dispersed to combat flames, there's probably an impact to the aquifer,” Baird said.

The very next day a fire broke out in Highlands. It was small enough that firefighters were able to put it out with water, the incident triple-underlined that his concern is legitimate.

Finally, there is a worry about demand. “Longer, hotter, drier summers mean that we're using water longer than we normally would have. So we're having higher withdrawals from the aquifer.”

A natural increase to how much water people use from the aquifer is compounded with added users, as places that don’t have access to CRD piped water continue to be developed.

There’s also quite a variety in how much water each household uses.

“I've got customers that order water every three weeks, and I've got customers that order water every seven weeks. It’s all about water usage: how many times to flush your toilet? How many times do you do laundry? How long are your showers?” Leslie said.

Customers who rely on a temperamental aquifer such as the 606 will quickly notice the impact from climate change as summers are drier and rain is erratic. They will notice it, if nowhere else, in their wallets.

“It's not cheap for me to truck water. It’s anywhere from $240 on a quick delivery that's five minutes up the road, upwards of $400 for an hour away,” Leslie said. Even though he’s in it to make money, "I'm not about soaking people either, pun intended.”

He advises customers on how to reduce their water usage. Modern appliances and low-flow toilets reduced some customers from a three-week interval to seven weeks between refills.

“You don't realize how much is going down the drain until you're buying the water. Like, holy shit, I just went through 3,200 gallons in freakin’ two weeks. Like, it's a lot of water.”

The 606 is relatively small, along with most of BCs aquifers

The larger an individual aquifer is, the more attention it gets from the government, Wei said. There are some aquifers in the US and eastern Canada that support billions of dollars of activity.

But BC’s geology creates relatively small aquifers: the 606 is 537.6 square kilometres, and the 680 is 209 square kilometres. Compared to the St. Lawrence watershed of several thousand square kilometres.

“Protection is tied to the economy, right. So when you have 30 farms over an aquifer, that's very different from the Ogallala Aquifer, where the states of New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Nebraska rely on it for their agricultural economy. Or the St. Lawrence watershed where you have major cities and industries. I mean, there's billions and billions of dollars within the St. Lawrence watershed. Therefore, you put the money to make sure it's okay,” Wei said.

“But who's going to put money into a tiny little creek or a tiny little aquifer? I think part of it is the underestimation that these individual aquifers aren't that important. But if you don't have a way of managing them across the board, sure, you could let one little one die. But you know, if one little one dies, all the little ones start to die.”